Latest News

Soaring German housing costs leave Merkel vulnerable

October 29th 2018

By Financial Times

Michael Boedecker has lived in Frankfurt’s Ostend district for more than two decades, and has watched the area’s transformation with growing dismay.

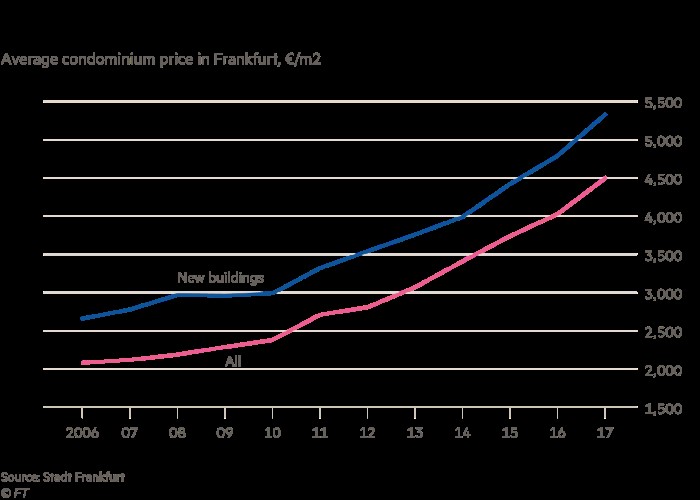

House prices and rents in the former working-class neighbourhood have soared in recent years. Standing in the October drizzle on a weekday afternoon, Mr Boedecker points to a building a few doors down from his own. A rental apartment has come on the market there for almost €20 per square metre — more than double what he and other long-term residents are paying.

“All this used to be cheap housing,” said the Frankfurt pensioner. “But now it is being cleared out bit by bit.”

One reason for the Ostend boom can be found just across the road, where the gleaming twisting tower of the European Central Bank rises into the sky. The arrival of the ECB in 2014 unleashed a flood of investment into this previously neglected part of Frankfurt. Though parts of Ostend remain scruffy, the area is dotted with pricey apartment blocs, elegant restaurants and designer furniture stores.

But laments such as Mr Boedecker’s can be heard in cities across Germany. The scarcity and cost of housing have become a new hot-button issue for voters and politicians alike. In Hesse, the federal state that surrounds Frankfurt, housing has emerged as a notable vulnerability for its conservative-led government ahead of Sunday’s regional election.

In Berlin, Chancellor Angela Merkel held a “housing summit” last month to discuss ways to alleviate the housing shortage and help Germany’s hard-pressed tenants. One of the meeting’s key conclusions: the country needs 1.5m new flats over the next four years.

Lurking behind such figures are vast discrepancies between subdued rural areas and booming cities such as Munich, Berlin, Frankfurt and Cologne, where the housing shortage and rental squeeze are most acute. “This is no longer just a concern for low-income households. The problem has reached the middle of society: even teachers and lawyers now struggle to find affordable housing,” said Mike Josef, the head of planning and housing in Frankfurt’s city government. He estimated that the city — whose population has risen by more than 100,000 over the past decade — had a shortfall of about 40,000 flats.

Thorsten Schäfer-Gümbel, the leader of the opposition Social Democrats in Hesse, said the current housing shortage was to a large degree the result of political decisions made by Christian Democratic governments over the past two decades. “One of the reasons [for the lack of affordable housing] is that the federal state privatised and sold 60,000 flats from the public stock and three out of four public housing companies,” he says.

Even in his home village of Lich, 60km north of Frankfurt, building land sells for up to €400 per square metre. “Compared to London that is nothing, but for Hesse that is a quite a number,” Mr Schäfer-Gümbel said.

Analysts say Germany’s current housing problem has its roots in the years after the turn of the millennium, when policymakers became convinced that the main challenge for city planners was the management of population decline. New housing starts fell dramatically. At the same time, local and state governments sold down their social housing stock and stopped investing in new affordable homes.

“The state failed to do its homework in the run-up to the current housing crisis,” said Claus Michelsen, an economist at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) in Berlin. “In the 2000s, there was lots of talk about the ageing of society and population decline, but not much about the trend towards urbanisation. The state should have made available land for new construction and invested in social housing. But that was neglected.”

The city of Frankfurt still has more than 30,000 social housing units under public management, down from 73,000 three decades ago. The waiting list, however, currently runs to 10,000 households. The broader problem of affordable housing, officials say, is made worse by the trend towards luxury conversions of existing apartment blocs. Under German law, developers can recoup a part of their investment in renovations by raising rents — sometimes by 40 per cent or more.

Not far from Mr Boedecker’s own apartment bloc is a freshly renovated stuccoed building that has seen precisely that development. “All the old tenants are gone,” he said. “This part of the Ostend is changing rapidly. And if nothing is done about it, the displacement will just go on.”

Some fear that the housing shortage in large German cities will have profound social consequences. “Housing is the core of what people mean by social security,” said Daniel Mullis, a member of the Frankfurt social movement Stadt für Alle — or City for All. “Your home is where your friends are, where your school is. If you are forced to leave your neighbourhood you don’t just lose your flat — you often lose your social circle and become more isolated.”

At a time when Frankfurt is bracing itself for a Brexit-induced influx of well-paid bankers and consultants from London, the housing debate has re-focused political minds in the city. Mr Josef said the city government was doing what it could to protect long-term residents in vulnerable areas such as Ostend, but admitted the measures would take years to bear fruit: “We have to create the conditions now to avoid having a situation like in London 10 or 15 years from now, where normal people can no longer afford to live in the inner city.”